by Larry H. Maxey, founder and superintendent, NAILE Fullblood Simmental Shows

Our Pioneers — Cattle Town

As we ended the last column about the American Bison, it was noted that the following edition would focus on the creation of what would become known as “Cattle Towns.” In his book Cattle Kingdom, Christopher Knowlton provided the background for this novel idea. In retrospect, the concept was so simplistic in form that historians in later years seemed surprised that the occurrence was overlooked by the most powerful and wealthiest business leaders of the mid-1800s. Yet, one young man would forge his own path in the cattle business seeing opportunities others missed.

Joseph G. McCoy was a young Illinois cattle merchant. With the railroads moving farther into the Great Plains, he realized that there were no railroad depots set up specifically for the sale of cattle. He set out to change that. In partnership with his two brothers, his idea was to build a small town to receive the cattle herds and wrote, “the Southern drovers and the Northern buyer would meet on equal footing and both be undisturbed by mobs or swindling thieves.” It was, according to historian Paul Wellman, “one of the great single ideas of this nation’s history.”

In the spring of 1867, McCoy pitched his idea to several railroads and was rejected by all with most proclaiming they wouldn’t waste a dollar on such foolishness. Undeterred, McCoy finally received a commitment from the very small Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad. If McCoy could put his plan in action, they agreed to ship cattle to Chicago via Quincy, Missouri, at the agreed-upon rate of 40 dollars per stock car. The agreement, according to McCoy, helped lay the foundation for the creation of Chicago’s primacy as the cattle hub of the west, and eventually the nation’s headquarters of the meatpacking industry.

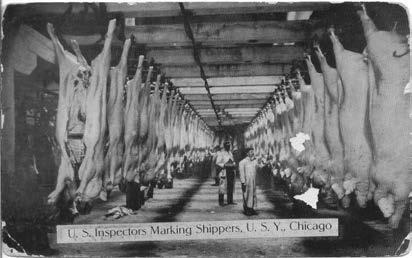

Meat inspectors in Chicago marking beef carcasses before shipping.

Now he had to build that “Cattle Town.” After much deliberation, he chose a small Kansas hamlet and stage station named Abilene, which only had a dozen or so dirt-filled log huts, which he later described as “a very small dead place.” In June 1867, with money from his family, construction began. Within two months, a cattle yard that could hold 3,000 head had been built. Two ten-ton Fairbanks scales were set up that could weigh 20 cattle at a time. Construction of the famous three-story hotel, the Drovers Cottage, was begun, along with other accommodations.

He was ready to start receiving cattle. Using his contacts back East, they alerted the Springfield and Chicago cattle buyers of this new and bold opportunity. Trail bosses in the south were persuaded to bring their cattle to Abilene.

By the fall of 1867, around 35,000 cattle arrived in the Abilene yards with 20,000 shipped out by railroad. Now those same “big” railroads that once rejected his idea came calling. They wanted in on this action but many were now rejected by McCoy. Those McCoy favored built siding areas handling up to 100 cars for loading cattle. McCoy’s cattle pens were named the Great Western Stockyards, and were able to hold or load 20 cars an hour with 18 steers per car. Each year, business doubled. McCoy had just created the first “cattle town.” His business model was copied repeatedly. Cattle towns were built all over the West with virtually every famous town in Western lore among them.

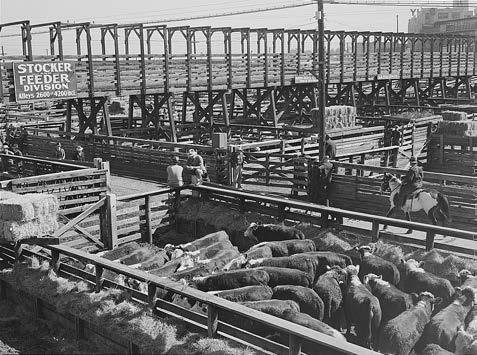

The Denver Stockyards in 1939. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Hopefully, now we can appreciate the basis for why so many of our cities that remain today began as a lowly “cattle town.” They were the result of a simplistic idea often rejected as pure “nonsense” that was pursued by a “foolish” young man who wouldn’t give up. Perseverance, indeed, and another fine example of the American and “Pioneer” spirit so fitting for this column. .

Editor’s note: This is the forty-seventh in the series Our Pioneers.

Is there a Simmental pioneer who you would like to see profiled in this series? Reach out to Larry Maxey or the editor to submit your suggestions: